Alford contribution to Sang-Hyun Song volume

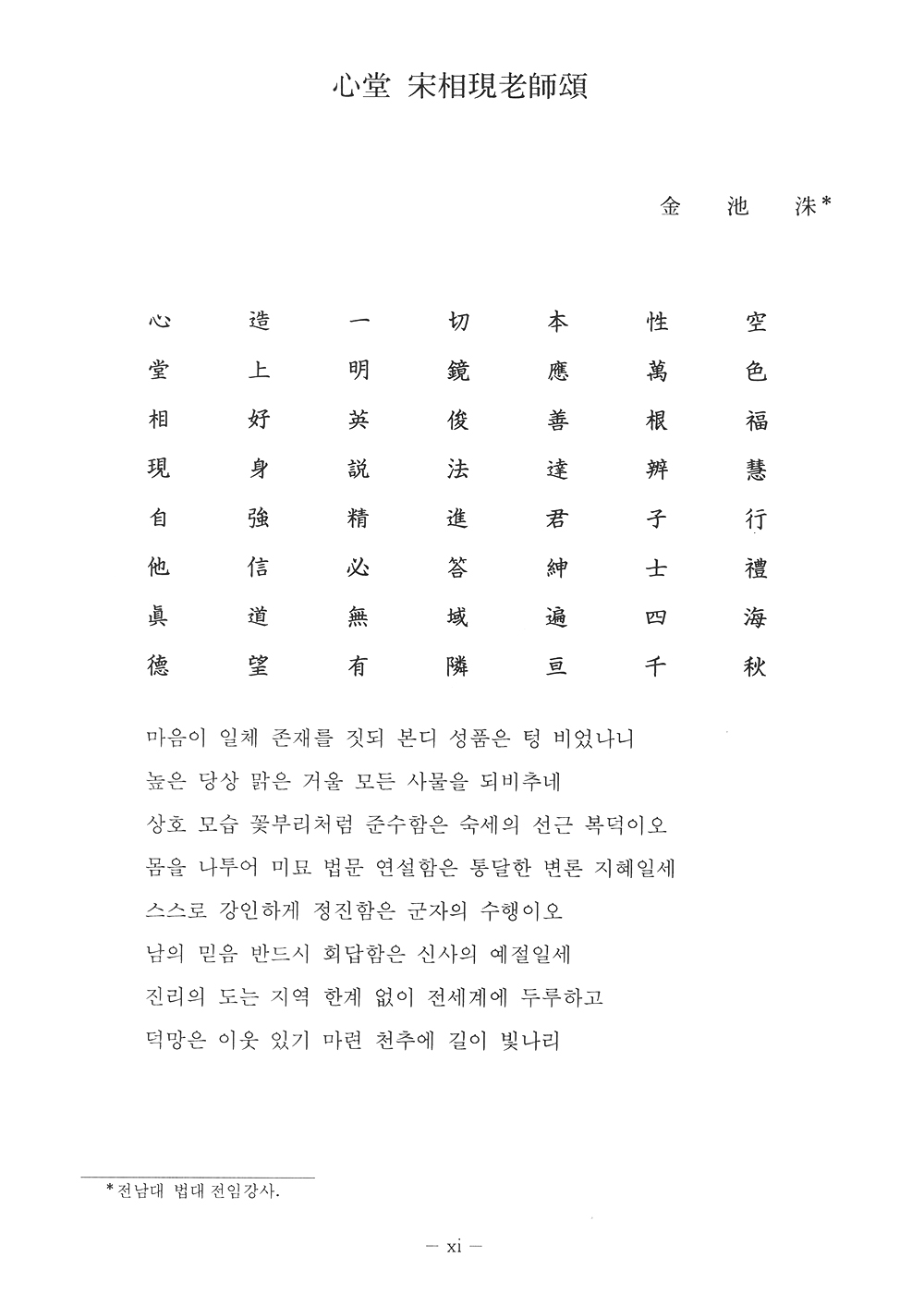

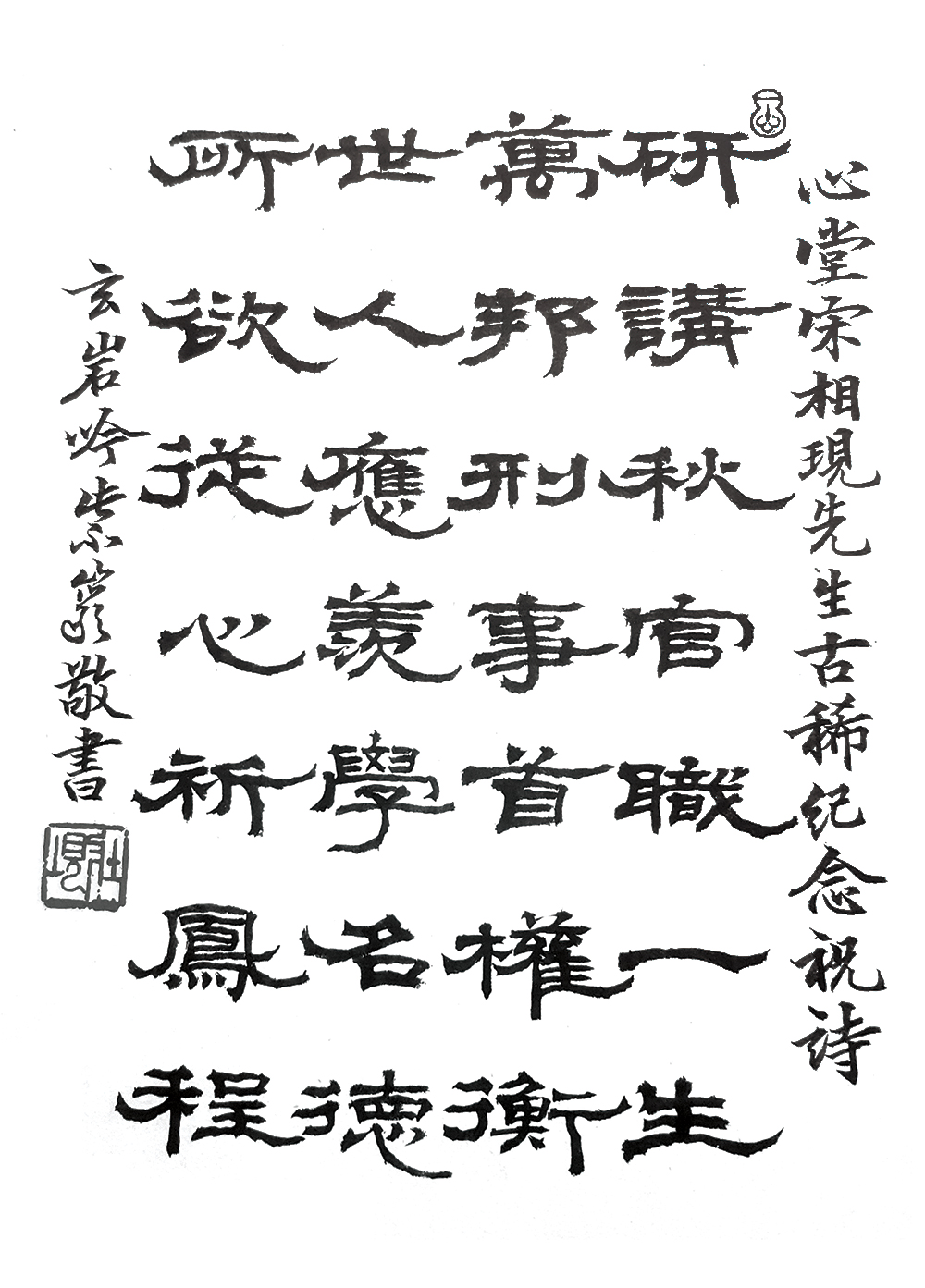

It is no small challenge to try to write an appropriate tribute for Professor Sang-Hyun Song. One’s mind is immediately flooded with images of the Renaissance man or an idealized vision of an Yi dynasty yangban or the lawyer-statesman, to employ a more contemporary term. That welter of powerful images, each worthy in itself but none fully adequate, is as it should be, for Sang-Hyun Song is truly a singular figure . And the particular occasion of his sixtieth birthday makes the task even more daunting, as on the one hand, it seems hard to believe that Professor Song is only sixty, given how much he has managed already to accomplish while on the other, it seems hard to believe that he could already be sixty, given his youthful vigor and spirit.

Sang-Hyun Song is, of course, first and foremost a scholar in the truest meaning of the word, a man committed to uncovering and conveying the truth, illustrating in his person the Confucian admonition that at sixty, my ear obediently received the truth (liushi er er shun). At home in Korea, he has, of course, been a landmark figure, starting from the time that he overcame the skepticism of some to become the first byonhosa to join a law faculty, ranging through his years as a member of the faculty of the Seoul National University College of Law, and culminating in his tenure as dean of the College. Over that period and still, he has produced important scholarship covering an array of areas in the civil law and beyond, nurtured many of Korea’s finest younger academics, and guided his beloved alma mater and Korean legal education more broadly.

His impact abroad has been no less. He has been an ambassador in this country and far beyond for Korean law and society, doing more than anyone of his generation to acquaint us with the wonders (and the occasional rough spot) in Korea’s long and rich history regarding legal institutions. It is no exaggeration to say that we at Harvard have had no better visiting professor from abroad (as evidenced by the fact that we have happily had here in that role multiple times) while at New York University, he has given definition to the term Global Professor.

What has touched me the most, however, has not been these achievements, as grateful as I am for them, nor Professor Song’s myriad other public accomplishments (such as his years of wise counsel regarding law and education to officialdom), but his more human and perhaps less obvious qualities. For all the conviction with which he holds his beliefs, I have constantly been struck by Professor Song’s willingness to recognize and nurture talent, even in those whose views might have diverged from his own (which generosity of spirit is not, alas, a quality that I see widely enough shared among other scholars, in my country or elsewhere, of his stature). And no less importantly, I have been and am still moved as I think of the extraordinary lengths to which Professor Song routinely went during his time at Harvard to educate and assist even the rawest of undergraduates coming for the first time to Korean issues and the parental-like pride he took in their subsequent learning. It was not uncommon, for instance, during his visits at Harvard to find him capping off a long day of teaching and many extra office hours by hosting groups of students for meals to continue the educational dialogue.

And so, it is a privilege to be able to participate in this tribute to so fine a scholar and person. Thank you.

Professor, Harvard University

Director, East Asian Legal Studies Program

Henry L. Stimson Professor of Law

Director, East Asian Legal Studies Program

Henry L. Stimson Professor of Law

E-Mail: alford@law.harvard.edu